‘The Brandenburg Beckett’: the last living link to German theatre’s golden age

He has been called ‘the German Orson Welles’ and carries the torch of political theatre lit by Bertolt Brecht. As Edinburgh prepares to stage Man to Man, his play about a woman forced to pass as her husband, the great writer Manfred Karge talks about class war, capitalism and why Hitler films are boring

Monday 3 August 2015 18.53 BST

Shares

Comments

It’s late afternoon, the matinee performance has just finished, and tourists are now swarming round the legendary Berliner Ensemble theatre, looking straight through the old man drifting about in checked shirt and tracksuit bottoms, unaware that he’s the last living link to the golden era of German stage. Only a few budding actors stop, whisper and stare in awe at Manfred Karge and his great silver mane.

Karge, now 87, has been called “East Germany’s Orson Welles” or “the Brandenburg Beckett” – though those aren’t comparisons he is comfortable with. “Don’t get me wrong,” he says, as we take our seats in the theatre’s sweltering beer garden, “I wouldn’t want to compare myself to Beckett. As a playwright, I was always the opposite. Beckett knew exactly how he wanted his plays to be performed. Mine don’t even have stage directions.”

Given such a lack of authorial ego, it seems even more remarkable that, when Karge eventually departs the stage for good, he’ll leave behind at least one of the great modern classics of European theatre. Man to Man was originally written in the summer of 1982 as a favour to Lore Brunner, Karge’s Austrian partner, a veteran ensemble-player who had always wanted a solo piece. An urban legend, relayed by a friend, served as the premise: in the middle of Weimar Republic-era depression, Ella Gericke assumes the identity of her deceased husband Max in order to hold on to his job as a crane operator, precariously manoeuvring around a world of sweat, machismo and cheap liquor.

Only years after the play had premiered in Bochum, in December 1982, did Karge receive a newspaper cutting in the post that showed that his play was in fact based on a true story: the real Ella had managed to keep up her act for a total of 12 years. “And I thought I had merely been claiming the privilege of literature to show her deception as such a perfect act.”

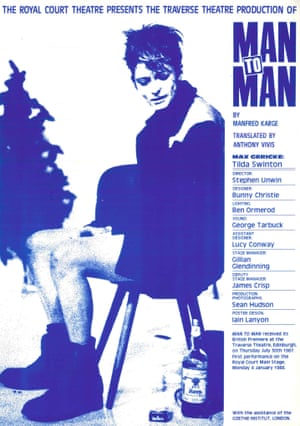

A 1987 production of the play, at the Traverse in Edinburgh, launched the career of Tilda Swinton: her cross-dressing masterclass in a film version five years later led to Sally Potter casting her in Orlando. Man on Man lived on even after Brunner died in 2002: by Karge’s own reckoning, it has been performed “on nearly every continent”, with new productions currently showing in Stockholm, Amsterdam, Johannesburg, Budapest and Istanbul.

And there’s another new adaptation opening this week at the Edinburgh festival. In the 1980s, part of the appeal of Karge’s monologue was that it breathed new life into a dying genre: working-class theatre. “Almost all of the 15 plays I have written are about little people,” he says. “I have never been interested in the lives of kings and queens. All those films about Hitler, they just bore me: we all know the Nazis at the top were pigs. To me, the most interesting thing about the Nazi period is how the working-class people coped.”

In Ella Gericke’s case, coping with National Socialism requires the same cold-hearted pragmatism that led her to assume her husband’s identity. In one scene, the dialogue describes the grey walls of a cell: we assume Gericke has been caught out and ended up in prison – until we realise that she is not the prisoner, but the guard. To dodge the draft, Karge’s cross-dressing anti-hero has joined the Nazis’ paramilitary arm, the SA.

But while Man to Man is unmistakably a play about working life, it rises above kitchen-sink realism, mixing working-class slang with expressionist poetry and Goethe quotation, all the while pursuing a question that remains relevant even in 2015: if human beings under capitalism are solely defined by their employment status, does their gender, personality, and emotional life matter at all? Bertolt Brecht’s short story The Job, based on the same true-life story as Man to Man, puts it succinctly: “Woman became man within days, via the same route that man had become man over the course of millennia: the process of production.”

Can you still make plays about working-class struggles when your paying audience is made up of a much wealthier segment of society? “The middle classes,” says Karge, “are interested in these struggles because they always worry about losing their status and slipping down the pecking order. But, of course, it is a problem for playwrights interested in working-class life that we don’t always have the audience we wish for. It was different back when the Berliner Ensemble first opened. You had whole factory brigades or school classes going to the theatre. A ticket used to cost 1.50 East German marks. Now people pay €40.”

Brecht has been a constant presence in Karge’s career, even though the two men never met. Born in the Brandenburg region in 1938, Karge was talent-spotted by the playwright’s second wife Helene “Helli” Weigel while still at drama school and asked to join the cast at the Berliner Ensemble, where he stayed for an initial nine-year stint, then returned for good in 1993. Originally set up by the administrators of the Soviet-occupied zone to invigorate East Berlin’s cultural life, the theatre became a militant bastion of Brechtian philosophy after his death in 1956: a cultural temple dedicated to preserving the idea of epic theatre, which maintained that audiences should not be fooled into empathy by the empty trappings of realism, but jerked into critical reflection, if not action.

If one were to believe the ensemble’s outgoing director, that original spirit is currently more under threat than ever, particularly by the kind of postmodern showmanship that many veterans fear will be imported to the city by the new head of Berlin’s experimental Volksbühne theatre, ex-Tate Modern director Chris Dercon. “We are currently witnessing European theatre’s Waterloo,” Claus Peymann recently told German weekly Die Zeit, “and sadly Germany has become the main battlefield.”

Karge is decidedly less terrified. The strict rules of epic theatre may have been what first attracted him to Brecht, but he found breaking them easier than many people do now. In his first year at the ensemble, he and a friend convinced Weigel to let them put on Brecht’s opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, only to find that the Songspiel version he wanted to stage had been lost in the archives. So Karge simply wrote a “Brecht-sounding” script around the songs and put on the show, only confessing the extent of his poetic licence to Weigel after the premiere had been a success.

In the late 1960s, Karge and some others left because they felt the theatre was interpreting its founding father’s work too literally. They began practising Brechtian theatre – but without Brechtian plays – at other venues around Germany, as the playwright’s relatives were withholding performance rights. Brecht’s theatre, Karge says, has always been less about theorising than about boiling things down to basics. “What I learnt from Brecht is that every performance starts from zero. Brecht never tried to confuse people – he wanted to tell stories and be understood.”

He goes on: “I still notice a difference between actors who started out in West Germany and those who were trained in the East. The western actors are often trying to express their inner state: their acting is less about telling a story than discovering yourself. In the east, our training was much more focused on technique.” Even now, he says, members of the audience come up to him after shows to praise him for his elocution.

Is Brecht’s idea of epic theatre still relevant? “It is – because the subjects Brecht was interested in are still alive. That’s not necessarily good news for Brecht: he might have been happy to find out that the problems he was interested in are no longer around. If there was no more capitalism, Saint Joan of the Stockyards wouldn’t need to be performed. But it’s all still here, that’s the mad thing. We are going in circles. The excesses of capitalism aren’t dying down – they are getting worse and worse. And until that stops, Brecht remains relevant.”

Man to Man is at Underbelly Potterrow, Edinburgh, 5-31 August