Today marks the 45th anniversary of the death of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton. On December 4, 1969, Chicago police raided Hampton’s apartment and shot and killed him in his bed. He was just 21 years old. Black Panther leader Mark Clark was also killed in the raid. While authorities claimed the Panthers had opened fire on the police who were there to serve a search warrant for weapons, evidence later emerged that told a very different story: that the FBI, the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office and the Chicago police conspired to assassinate Fred Hampton. In this 2009 interview from the Democracy Now! archive, Amy Goodman and Juan González speak with attorney Jeffrey Haas, author of The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Today marks the 40th anniversary of the death of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton. On December 4th, 1969, Chicago police raided Fred Hampton’s apartment, shot and killed him in his bed. He was just 21 years old. Black Panther leader Mark Clark was also killed in the raid.

While authorities claimed the Panthers had opened fire on the police who were there to serve a search warrant for weapons, evidence later emerged that told a very different story: that the FBI, the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office and the Chicago police conspired to assassinate Fred Hampton. Noam Chomsky has called Hampton’s killing “the gravest domestic crime of the Nixon administration.”

Today, on this 40th anniversary of his death, we spend the rest of the hour on Fred Hampton. In 1969, he had emerged as the charismatic young chairman of the Chicago Black Panther Party. This is some of Fred Hampton in his own words.

FRED HAMPTON: So we say—we always say in the Black Panther Party that they can do anything they want to to us. We might not be back. I might be in jail. I might be anywhere. But when I leave, you’ll remember I said, with the last words on my lips, that I am a revolutionary. And you’re going to have to keep on saying that. You’re going to have to say that I am a proletariat, I am the people.

A lot of people don’t understand the Black Panthers Party’s relationship with white mother country radicals. A lot of people don’t even understand the words that Eldridge uses a lot. But what we’re saying is that there are white people in the mother country that are for the same types of things that we are for stimulating revolution in the mother country. And we say that we will work with anybody and form a coalition with anybody that has revolution on their mind. We’re not a racist organization, because we understand that racism is an excuse used for capitalism, and we know that racism is just—it’s a byproduct of capitalism. Everything would be alright if everything was put back in the hands of the people, and we’re going to have to put it back in the hands of the people.

With no education, the people will take the local foundation and start stealing money, because they won’t be really educated to why it’s the people’s thing anyway. You understand what I’m saying? With no education, you have neocolonialism instead of colonialism, like you’ve got in Africa now and like you’ve got in Haiti. So what we’re talking about is there has to be an educational program. That’s very important. As a matter of fact, reading is so important for us that a person has to go through six weeks of our political education before we can consider himself a member of the party able to even run down ideology for the party. Why? Because if they don’t have an education, then they’re nowhere. You dig what I’m saying? They’re nowhere, because they don’t even know why they’re doing what they’re doing. You might get caught up in the emotion of this movement. You understand me? You might be able to get them caught up because they’re poor and they want something. And then, if they’re not educated, they’ll want more, and before you know it, they’ll be capitalists, and before you know it, we’ll have Negro imperialists.

We don’t think you fight fire with fire; we think you fight fire with water. We’re going to fight racism not with racism, but we’re going to fight with solidarity. We say we’re not going to fight capitalism with black capitalism, but we’re going to fight it with socialism. We’re still here to say we’re not going to fight reactionary pigs and reactionary state’s attorneys like this and reactionary state’s attorneys like Hanrahan with any other reactions on our part. We’re going to fight their reactions with all of us people getting together and having an international proletarian revolution.

Black people need some peace. White people need some peace. And we are going to have to fight. We’re going to have to struggle. We’re going to have to struggle relentlessly to bring about some peace, because the people that we’re asking for peace, they are a bunch of megalomaniac warmongers, and they don’t even understand what peace means. And we’ve got to fight them. We’ve got to struggle with them to make them understand what peace means.

Bobby Seale is going through all types of physical and mental torture. But that’s alright, because we said even before this happened, and we’re going to say it after this and after I’m locked up and after everybody’s locked up, that you can jail revolutionaries, but you can’t jail the revolution. You might run a liberator like Eldridge Cleaver out of the country, but you can’t run liberation out of the country. You might murder a freedom fighter like Bobby Hutton, but you can’t murder freedom fighting, and if you do, you’ll come up with answers that don’t answer, explanations that don’t explain, you’ll come up with conclusions that don’t conclude, and you’ll come up with people that you thought should be acting like pigs that’s acting like people and moving on pigs. And that’s what we’ve got to do. So we’re going to see about Bobby regardless of what these people think we should do, because school is not important and work is not important. Nothing’s more important than stopping fascism, because fascism will stop us all.

AMY GOODMAN: The words of Fred Hampton, those excerpts courtesy of the 1969 documentary The Murder of Fred Hampton, produced by the Chicago Film Group. After Hampton was killed, Black Panther leader Bobby Rush spoke at his funeral about his life and legacy.

BOBBY RUSH: We can mourn today, but if we understood Fred and we are dedicated that his life wasn’t given in vain, then there will be no more mournings tomorrow, then all our sorrow will be turned into action. He said, “But you have to remember one thing, and that’s ‘be strong.'” He wasn’t afraid of anything.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Black Panther and now Chicago Congressman Bobby Rush.

For more on Fred Hampton’s life and death, we’re joined in our Democracy Now! printing press studio by attorney Jeffrey Haas. He is the author of a new book called The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther. In 1969, Jeffrey Haas co-founded the People’s Law Office, whose clients included the Black Panthers, SDS—that’s Students for a Democratic Society—and other political activists. He was the attorney for the plaintiffs in a federal suit, Hampton v. Hanrahan, filed against the Chicago police, the prosecutor, and later the FBI.

We welcome you to Democracy Now!

JEFFREY HAAS: Thank you. Good to be here.

AMY GOODMAN: So, go back in time with us 40 years ago. Where were you when Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were gunned down in their beds in Chicago by the police?

JEFFREY HAAS: Forty years ago this morning, I got a knock on my door at 7:30 in the morning. It was my partner, Skip Andrew, who happened to live up the street from me. When I opened the door, he was already dressed in a suit and tie and said, “The chairman’s been killed. The pigs vamped on his crib this morning.” And I couldn’t believe it, because I had seen Fred just two days earlier in the office, bigger than life, giving orders, talking about the breakfast program, talking about political education classes. I looked at Skip, and I was, as I said, somewhat—totally taken by surprise. And Skip said, “I’m going to go to the apartment.” And I said, “Well, what do you think I should do?” And he said, “Why don’t you go interview the survivors?” And with that, he was gone. And I thought, “Wow! Here’s this guy who was bigger than life, and all of a sudden he’s dead.”

So, that morning, which was exactly 40 years ago this morning, just about this time, I went to see the survivors. It turned out that Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were killed in the police raid, four other Panthers were shot, were at the hospital, and the three who were only beaten up were at the Wood Street police station. So I—Hanrahan had given orders—Hanrahan, the police were assigned to him—not to allow anyone to see them. But I sort of worked my way through that.

And the first person I saw was Deborah Johnson. She was Fred Hampton’s fiancée, and she was eight-and-a-half months pregnant with their child. So, very much like this table, although a smaller one, I was sitting there, and I looked at this woman, and she was still crying, and I said, “What happened?” And she said, “Well, the pigs came in shooting. We were in our bed. I got on top of Fred at one point to try to protect him. Somebody pulled me out of the room. After I was pulled out of the room, two policemen entered the room, and one of them said, ‘Is he dead yet?’ I heard two shots, and then the other one said, ’He’s good and dead now.’”

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to leave it there for a moment, break and come back, and then hear from Deborah herself. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. Back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: On this 40th anniversary of the FBI and police killing of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, Black Panthers in Chicago, we’re going to turn right now to Deborah Johnson. Deborah Johnson was the fiancée of Fred Hampton. She was in bed with Fred when the police raided the apartment. She was, well, more than eight months pregnant. This is how she described the raid. Her son Fred Hampton Jr. is sitting on her lap as she describes how his father was killed.

DEBORAH JOHNSON: Someone came into the room, started shaking the chairman, said, “Chairman, Chairman, wake up. The pigs are vamping.” Still half asleep, I looked up, and I saw bullets coming from, it looked like, the front of the apartment, from the kitchen area. They were—pigs were just shooting.

And about this time, I jumped on top of the chairman. He looked up. Looked like all the pigs had converged at the entranceway to the bedroom area, back bedroom area. The mattress was just going—you could feel bullets going into it. I just knew we’d be dead, everybody in there. When he looked up, just looked up, he didn’t say a word. He didn’t move, except for moving his head up. He laid his head back down, to the side like that. He never said a word. He never got up off the bed.

The person who was in the room, he kept hollering, “Stop shooting! Stop shooting! We have a pregnant woman, a pregnant sister in here!” At the time I was eight-and-a-half, nine months pregnant. My baby was to be delivered in two weeks. Pigs kept on shooting. So I kept on hollering out. Finally, they stopped.

They pushed me and the other brother by the kitchen door and told us to face the wall. Heard a pig say, “He’s barely alive. He’ll barely make it.” I assumed they were talking about Chairman Fred. Then they started shooting. The pigs, they started shooting again. I heard a sister scream. They stopped shooting. Pig said, “He’s good and dead now.” The pigs were running around laughing. They was really happy, you know, talking about Chairman Fred is dead. I never saw Chairman Fred again.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Deborah Johnson, the fiancée of Fred Hampton. On her lap, their little son, Fred Hampton, who is now an activist around prisoner rights and prisoner issues around this country.

Jeffrey Haas is our guest. He is author of The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther.

Talk about what came of that, after this day, 40 years ago.

JEFFREY HAAS: While I was interviewing the survivors, my partners went to the apartment. And when we gathered all the evidence, it turned out that the police had fired 90 shots into the apartment with a submachine gun, shotguns, pistols and a rifle. There was only one outgoing shot, and that came from a Panther who had been fatally wounded, and it was a vertical shot, after he was hit himself.

So, Hanrahan, who was—the police were assigned to the state’s attorney, a politically ambitious law-and-order prosecutor who wanted to get the political advantage of having attacked and taken out the Panthers, was on the TV that morning saying the Panthers opened fire. It turned out, we proved, that, quite to the contrary, it was a shoot-in, not a shootout.

What we uncovered years later—we also filed a civil rights suit after the charges were dropped against the Panthers. And in addition to proving, as I said, that it was a one-sided raid, that the police came in firing, the evidence also showed that Fred Hampton was in fact killed with two bullets, parallel bullets, fired into his head at point-blank range. He wasn’t killed with the bullets through the walls.

But what we uncovered was that the FBI had obtained a floor plan of Fred Hampton’s apartment. That floor plan was complete with all the furniture, including the bedroom where Hampton and Johnson slept and a rectangle showing the bed. And it turned out that this FBI informant, William O’Neal, and his control took that floor plan and gave it to Hanrahan’s raiders before the raid, so that they came in knowing the layout, knowing where Fred would be sleeping. And when we looked at the directions of the bullets, in fact, they converged on the bed where Fred Hampton was sleeping that morning.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: As I recall, a lot of the bullets were shot from the floor below, as well, as they were—

JEFFREY HAAS: No, they were most—they were from the front door and the back door, and then they took the one with the machine gun and stitched the wall in the front, and that went through all of the bedrooms in the apartment.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And the role of the FBI and of COINTELPRO, the FBI’s massive program against dissidents in the United States, how did you uncover that, as well?

JEFFREY HAAS: Well, first, there was a burglary at the Media, Pennsylvania, FBI office, in which some draft dodgers uncovered that there was this program that talked about—basically, it was an attack on the entire black movement and particularly on the Panthers. And it talked about disrupting, destroying and neutralizing the Panthers by any means necessary. And one of their objectives was prevent the rise of a messiah who could unify and electrify the black masses.

Fred Hampton, at 21, was a tremendously charismatic and powerful figure in Chicago. He could talk to welfare mothers, gang kids, and he could talk to law students and college students. He had the ability to pull people together. You got a little glimpse of that in what—the clip that you saw. But he made people believe in themselves. He made people feel powerful and that they could bring about change. And that was his real threat.

And so, we knew there was this program to prevent the rise of a messiah. We knew about the floor plan. Then we uncovered a document that they gave the informant a bonus after the raid, because his information was invaluable to the success of the raid. So, internally, the FBI actually took credit for this raid, for the results that Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were killed.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about Willie O’Neal.

JEFFREY HAAS: William O’Neal was the—when we—he was uncovered because he became a witness in another case. And I guess—we all knew William O’Neal. He was a very flamboyant person. And I guess my idea of an informant was somebody who sits quietly in the corner and takes mental notes. That was not William O’Neal. He was a provocateur. He built an electric chair that was supposedly to threaten potential informants in the party, when he was an informant. He attempted to build what he called a rocket that would go from the Panther office to City Hall until Fred Hampton—

AMY GOODMAN: Explain his position in the Black Panthers.

JEFFREY HAAS: He was the chief of security, and at one point he was Fred Hampton’s bodyguard. And he was present the night of the raid and left. And there was evidence that Fred Hampton was drugged. And he’s never admitted it, but some of that evidence suggests that O’Neal was the one who drugged him the night of the raid.

AMY GOODMAN: I want ask—just play for a minute a response—get your response to Cook County State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan. After the raid, he repeatedly claimed the Panthers had opened fire on the police. This is how he described what happened.

EDWARD HANRAHAN: The immediate, violent, criminal reaction of the occupants in shooting at announced police officers emphasizes the extreme viciousness of the Black Panther Party. So does their refusal to cease firing at the police officers when urged to do so several times.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: That was Ed Hanrahan, the Cook County state’s attorney. Your response to him? And also, what happened to Hanrahan as you sought to pursue the truth of the murder of Fred Hampton?

JEFFREY HAAS: When we gathered the evidence—and you can tell which way a bullet enters, from the smaller hole, and exits with a larger hole and the wood splayed outward—it became clear that, as I said, ninety shots came in, and at most one, a vertical shot, went out.

The Panthers were smart enough to invite the community in. The police never sealed it. And the black community, which had been divided on the Panthers, was not divided on the fact that a young man was murdered in his bed, a young leader, at 4:30 in the morning. So there was a tremendous reaction. And Hanrahan became defensive and told the story that you just saw.

And later on, he even went further and said, “Well, Fred Hampton personally was firing at the police.” And he gave the Chicago Tribune a photograph. The photograph had two black dots on it, and he says, “These are the gunshots that Fred Hampton fired.” We invited the press out there. It turns out those dots were nail heads.

And I think that was the beginning of the end of Edward Hanrahan. He never got elected to anything again. Even a Republican was elected state’s attorney of Cook County, which was unheard of. He ran for mayor. He ran for congressman. And basically his political career ended on December 4th, just at the time when he thought it would rise.

AMY GOODMAN: Juan, I want to talk about the overall context with Jeffrey Haas, but in 1969, I mean, you were one of the leaders of the Columbia student protests, one of the founders of the Young Lords. What was the effect 40 years ago today? Where were you on this day?

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, I remember very well the news coming about Fred Hampton’s death. And, of course, as you mentioned his ability to unite people, very few people are aware that Fred Hampton was the original creator of the concept of the Rainbow Coalition that Jesse—

JEFFREY HAAS: That’s correct.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —that a young Jesse Jackson then adopted later, because he was building unity between the Black Panthers and the Young Lords and some white radical organizations in Chicago, and he called them the Rainbow Coalition—

JEFFREY HAAS: That’s right.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —which is what Jesse then adopted into his main program. But he had this ability to unite all kinds of different groups, as you say, racial groups as well as across economic lines. And in terms of the legacy of Hampton—obviously Bobby Rush, who later became a congressman in Chicago, still is a congressman—what has been in Chicago the way that the political establishment has dealt with the reality of this assassination and of the historical impact of Fred Hampton?

JEFFREY HAAS: Well, I think, for one thing, it marked the independence of the black political leaders in Chicago, who had, up until then, had been pretty much lackeys of the mayor and the Democratic machine. And a young congress—a young state senator named Harold Washington spoke out, and Danny Davis spoke out, and Jesse Jackson welcomed Bobby Rush. And all of a sudden you had an independent and much more progressive black political machine, or part of the machine, that was independent. And I think that group and white liberals were given credit for eventually electing Harold Washington mayor, as Chicago’s first black mayor.

Of course, there’s also the legacy that, without a young leader, I think the West Side of Chicago degenerated a lot into drugs. And without leaders like Fred Hampton, I think the gangs and the drugs became much more prevalent on the West Side. He was an alternative to that. He talked about serving the community, talked about breakfast programs, educating the people, community control of police. So I think that that’s unfortunately another legacy of Fred’s murder.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And Jeff Haas, you talk in the book also about how you, a white radical raised in the South, ended up in Chicago that day as part of the People’s Law Clinic there, working with the Panthers. Could you talk about your own trajectory and how you got involved in this story?

JEFFREY HAAS: Well, I grew up in the South. I came from a progressive family, but also it was a segregated South. And I think being a white person there, we all accommodated ourself in some way to segregation. I think it made cowards of us all.

When I got to Chicago, I was influenced by what was going on nationally. Chicago was sort of the hub of all this political activity. You had the Democratic convention there. Dr. King had marched there. You had the conspiracy trial starting. You had the national office of SDS. All the forces were converging, and I was very much moved by the Black Power movement, the civil rights movement.

So we wanted to be lawyers for the people. We wanted to be—so we started the People’s Law Office in a sausage shop. And I think we started it with a sense of collectivity. So it wasn’t just me. There were four or five of us who, from the get-go, worked together.

And our mandate was to expose the murders, who the killers were of Fred Hampton. We did not know that it would take us to J. Edgar Hoover and John Mitchell and the seat of government. But, of course, it turned out that way. And the more we dug and the more we uncovered, the more interested we got and the more we realized that this was a national program. Some people have compared Hanrahan’s group to sort of a local hit squad, in order—but was utilized by the federal government and by Hoover. And I think, unfortunately, or not surprisingly, no one has ever done a day of time for the murder of Fred Hampton, for that raid. So I think another legacy is to try to hold our government officials accountable.

And interestingly enough, when the Church Committee in the ’70s began to investigate COINTELPRO—

AMY GOODMAN: We have 15 seconds.

JEFFREY HAAS: —as well as Watergate, it was Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld, Ford’s chief aides, who opposed any kind of exposure of this illegality or any kind of restraint on the intelligence committees.

AMY GOODMAN: We have to leave it there. I want to thank you very much for being with us, Jeffrey Haas. The Assassination of Fred Hampton is his book, How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther.

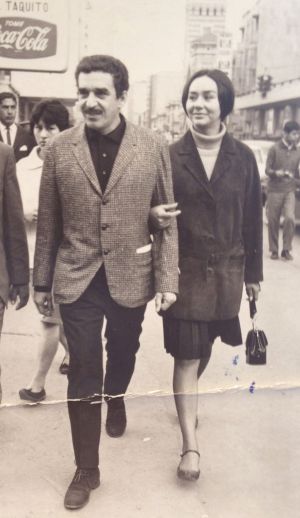

El Nobel colombiano Gabriel García Márquez y su esposa, Mercdes Barcha. / Imagen cedida por Harry Ransom Center

El Nobel colombiano Gabriel García Márquez y su esposa, Mercdes Barcha. / Imagen cedida por Harry Ransom Center

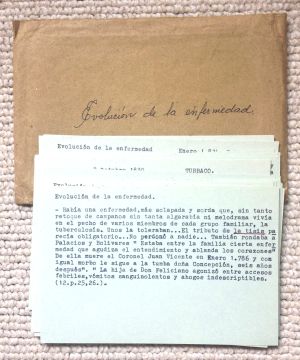

Fichas para el libro ‘El general en su laberinto’ de Gabriel García Márquez. / Imagen cedida por el Centro Harry Ransom

Fichas para el libro ‘El general en su laberinto’ de Gabriel García Márquez. / Imagen cedida por el Centro Harry Ransom

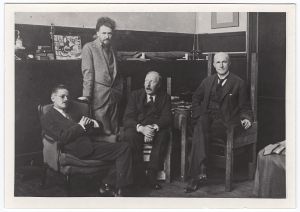

De izquierda de derecha, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Ford Madox Ford y John Quinn. / Imagen cedida por el Centro Harry Ransom

De izquierda de derecha, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Ford Madox Ford y John Quinn. / Imagen cedida por el Centro Harry Ransom

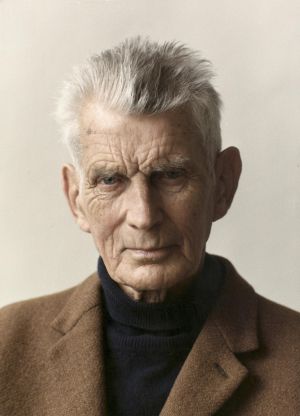

El escritor irlandés Samuel Beckett (1906-1989). / © Ullstein Bild / Roger-Viollet (Roger Viollet/Cordon Press)

El escritor irlandés Samuel Beckett (1906-1989). / © Ullstein Bild / Roger-Viollet (Roger Viollet/Cordon Press) Las pinturas rupestres en la cueva de Chauvet son vestigios de un tiempo marcado por narraciones orales.

Las pinturas rupestres en la cueva de Chauvet son vestigios de un tiempo marcado por narraciones orales.

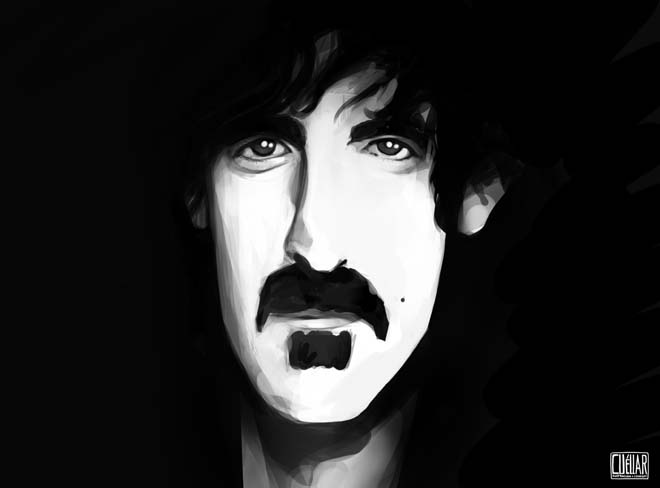

La verdadera historia de Frank Zappa

La verdadera historia de Frank Zappa

unta el coautor de la traducción de la autobiografía que se presenta el próximo 23 de octubre a las 19 horas en FNAC San Agustín (Valencia).

unta el coautor de la traducción de la autobiografía que se presenta el próximo 23 de octubre a las 19 horas en FNAC San Agustín (Valencia). para poder traducir al castellano su obra ha evolucionado positivamente hasta la publicación esta misma semana del título, aunque los responsables han cuidado mucho los detalles: “es la mejor adaptación a otro idioma, en tanto en cuanto que respeta todas las marcas tipográficas (cursivas, negritas…) y las ilustraciones tal y como se muestran en la versión original”, apunta Forés. Los autores han respetado incluso la portada.

para poder traducir al castellano su obra ha evolucionado positivamente hasta la publicación esta misma semana del título, aunque los responsables han cuidado mucho los detalles: “es la mejor adaptación a otro idioma, en tanto en cuanto que respeta todas las marcas tipográficas (cursivas, negritas…) y las ilustraciones tal y como se muestran en la versión original”, apunta Forés. Los autores han respetado incluso la portada.

About the Author: Bonnie J. M. Swoger is a Science and Technology Librarian at a small public undergraduate institution in upstate New York, SUNY Geneseo. She teaches students about the science literature, helps faculty and students with library research questions and leads library assessment efforts. She has a BS in Geology from St. Lawrence University, an MS in Geology from Kent State University and an MLS from the University at Buffalo. She would love to have some free time in which to indulge in hobbies. She blogs at the

About the Author: Bonnie J. M. Swoger is a Science and Technology Librarian at a small public undergraduate institution in upstate New York, SUNY Geneseo. She teaches students about the science literature, helps faculty and students with library research questions and leads library assessment efforts. She has a BS in Geology from St. Lawrence University, an MS in Geology from Kent State University and an MLS from the University at Buffalo. She would love to have some free time in which to indulge in hobbies. She blogs at the